A Five-Part Series

Part II: The Clinical Aspect

In our earlier blog entry, we posited that the term “population health” is rather meaningless unless stated in terms of how it is implemented, which involves the application of the clinical, organizational, and technical aspects of population health management. In this blog, we focus on the first of those three aspects.

If the key to achieving the “Triple Aim” is to address the social determinants of health for a defined population, as some have suggested, it is the providers on the front line who must create and deploy a plan of action. Hospitals are the logical focal point of healthcare in a community, and a hospital’s medical staff is on the front line of interaction with the individual patients who comprise the defined population. These hospital/physician teams logically become the “integrators” Dr. Don Berwick suggested must accept responsibility for organizing efforts to accomplish the Triple Aim.

Obviously, a new and intense level of cooperation is demanded of this team of administrators and providers. In the past, hospitals and their physician staffs were competing for the same healthcare dollars, but now collaboration to achieve efficiencies is demanded. Cuts in hospital reimbursement can only be accommodated with the help of physicians who work with hospital administration to find ways to reduce costs and maximize the effectiveness of hospitalization.

Physicians need hospitals, and vice versa. If these providers are going to have any impact on the social determinants of health, which we maintain they must, then other organizations and entities in the community serving the defined population must be engaged as well. Those contributing entities naturally will look to the hospital/physician organization as the integrator – the Organizational Hub – to lead a community discussion and issue a call-to-action focused on population health improvement.

Physician Engagement. There are many challenges to achieving the level of cooperation that is demanded. Certainly, physicians are essential to the process of shifting the focus of healthcare delivery from the existing episodic sick-care model to a system yielding value. But physicians often are the ones who are the most perplexed, depressed, overwhelmed, threatened, and downright angry about the direction healthcare delivery is headed. While physicians may, in their hearts, understand the need for change and concur with the ultimate goal, the process of getting there has many of them totally confused and defeated. Unfortunately, they don’t necessarily see the hospital as a natural ally.

One of the first steps necessary for hospitals to engage physicians is to repair any broken trust that may have arisen between the hospital and its medical staff. Such schisms are common. They must be confronted directly and reconciliation achieved before the hospital/physician Organizational Hub can provide any sort of meaningful leadership in the community to address the challenges of population health and its management.

Secondly, hospitals must address the challenge of sustaining physicians emotionally and financially while engaging them in the process of change. Emotional stability flows from having the ability to control one’s environment, and it is this very sense of loss of control that has physicians so out of sorts.

When we balance the enormous need to reinvent clinical processes with physicians’ need to gain control of their environment, the obvious answer for hospitals is to invite the physicians into a structured process that examines everything from clinical protocol to hospital procedures and business practices that are refocused on Triple Aim objectives. Physicians will engage if their ideas and opinions are valued.

The efficiency and effectiveness of clinical processes are at the heart of creating value. Only physicians can effectively drive the development and deployment of the most efficacious treatment protocol. Only physicians have the prestige and the opportunity to meaningfully engage patients in the process of managing their own health. Only physicians can meaningfully engage their peers in monitoring providers’ adherence to protocol and manage the efficiency with which care is delivered.

Physician Leadership. Identifying effective physician leadership is key to establishing a workable partnership between the hospital and its medical staff. Many healthcare organizations seeking to implement effective population health management strategies are calling upon a new C-suite leader, the Chief Population Health Officer (CPHO), to lead the Organizational Hub’s efforts. This relatively new position is often a physician executive who reports directly to the hospital CEO. He or she is charged with developing and implementing the Hub’s population health management strategy.

The CPHO job description includes responsibility for complex case management; overseeing disease management programs; implementing health risk assessments; devising wellness and lifestyle management strategies; developing health education programs; monitoring population health indicators such as patient activation, patient satisfaction, quality of life, actuarial analysis of risk evaluation methodologies; and overseeing managed care contracting.

Physicians have to be at the table when clinically integrated processes are developed, and they must accept the invitation to participate lest they have processes foisted upon them. It is not reasonable to expect every physician to participate actively in the role of planner and administrator of new clinical processes. Each physician, however, must at least accept responsibility for becoming aware of the dialogue and monitoring the change that is occurring around him or her.

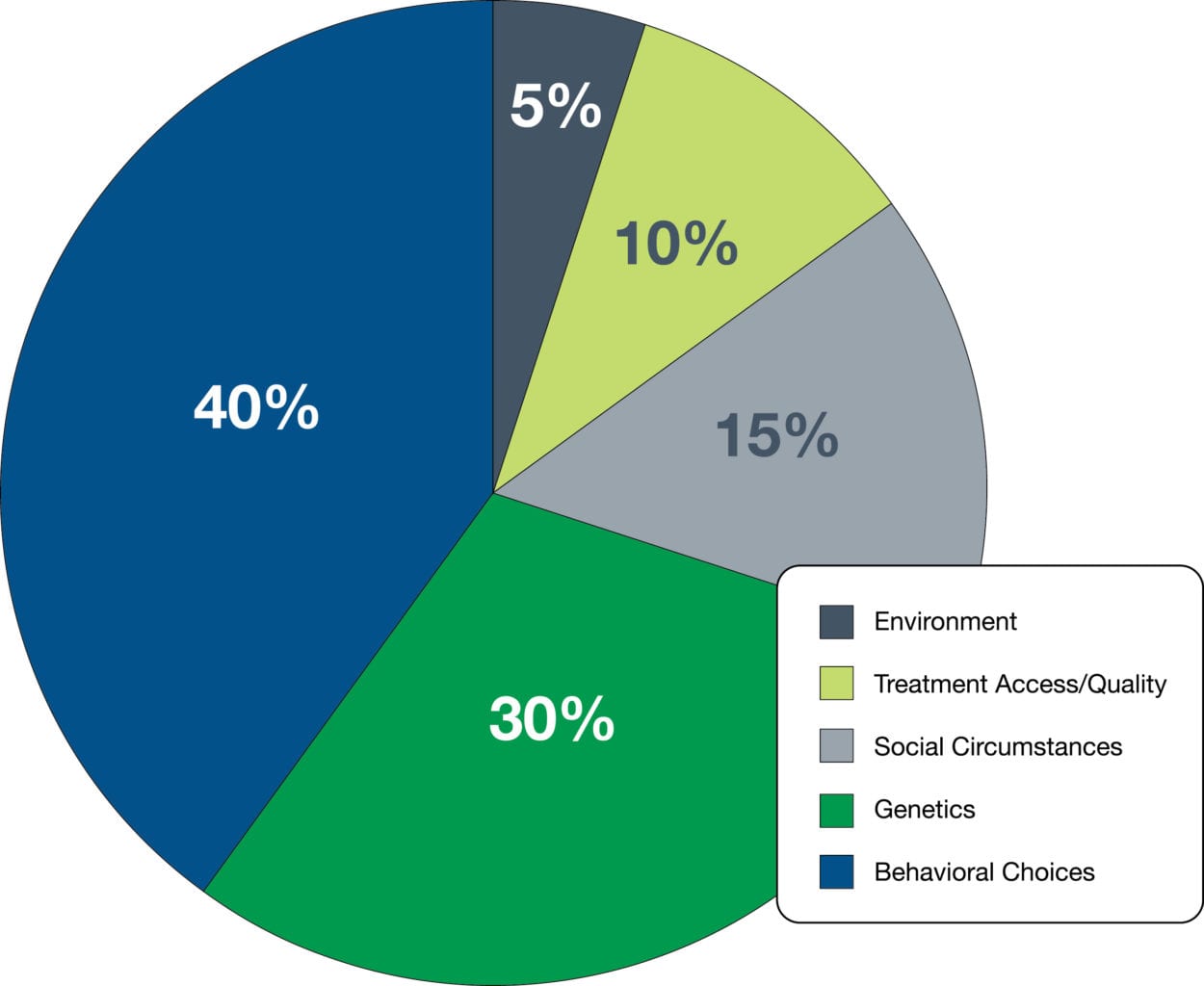

Expanding the Team. As physicians and hospital leaders begin their collaborative efforts, they also must realize that they are part of a much larger, very diverse team that is required to achieve improved population health. Access to quality medical treatment accounted for only 10% of a person’s health status. Behavioral choices such as diet, physical activity, and substance abuse; social circumstances such as education, employment, housing, crime exposure, and social cohesion; genetics; and environmental conditions all impact population health status far more profoundly.

It has been argued that one’s zip code may be more important to health and wellness than one’s genetic code. This concept is the underpinning of a new discipline known as healthography.

The Robert Woods Johnson Foundation has created city maps which highlight the enormous disparity in the status of nearby neighbors. For instance, babies born in Washington, D.C., separated by a few metro stops, may experience as much as a 7-year difference in life expectancy. Newborns in different neighborhoods in Kansas City, Missouri, can have a 14-year difference in life expectancy. Babies delivered in different New Orleans locations can be expected to show a 25-year difference in life expectancy.

To impact all these factors and improve population health status, the core team of physician and hospital leadership will have to involve a variety of other community stakeholders: therapists, behavioral health professionals, social workers, community healthcare organizations, educators, social service agencies, urban planners, law enforcement agencies, politicians, the judicial system, the faith community, restaurants, gyms, and retailers.

Improvement in population health will require engagement of all the social and medical systems that impact the quality of patients’ lives. It will have to consider the impact of healthography and determine the causes of the dramatic disparities it illustrates. The hospital’s CPHO logically should serve as the catalyst for community engagement and be tasked to develop meaningful relationships with community partners that traditionally have been ignored by healthcare leaders.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the expanded team of providers and community stakeholders must devise ways to engage the individual patients who comprise the population served to pursue improving their own personal health and healthy lifestyles. That may be the biggest challenge of all.

Patients have almost been trained to live in ignorance of the impact their lifestyle choices have on their health. Often, they live recklessly and expect simply to have health problems “fixed.” Environmental influences such as fast food ads, the size of soft drink cups, food portions served in restaurants, the tolerance of tobacco and drug use, movies and advertising that portray risky lifestyles, and the impact of poverty create strong headwinds of social mores that must be overcome to successfully achieve gains in population health. Patients need to know they have responsibility in this effort, and they must be encouraged to accept that responsibility.

When hospitals, their medical staffs, community partners, and stakeholders are brought into alliance to pursue population health improvement, the definition of population health will begin to crystalize. With sharpened focus, terminology will cease to be an obstacle to defining strategic objectives and developing realistic tactics that harness the power of providers to measurably improve the health status of the defined population they are serving.

Unfortunately, crystalized vision and unified effort are squandered without an effective organization to guide and direct the army of stakeholders required to effect change in a population’s health status. Next up, we will discuss the organizational aspects of population health as we continue exploring this elusive concept.

Next Up:

The Organizational Aspect of Population Health